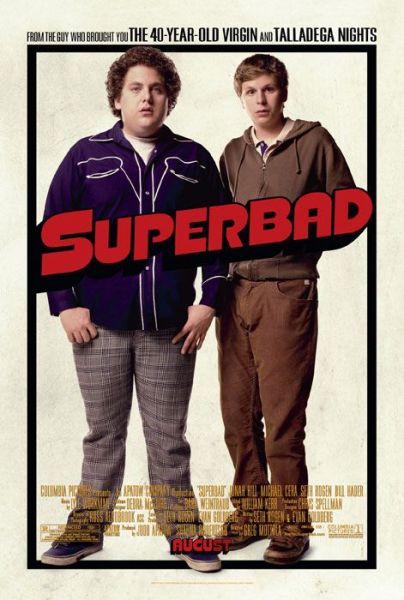

Superbad

Dir. Greg Mottola

Premiered August 17, 2007

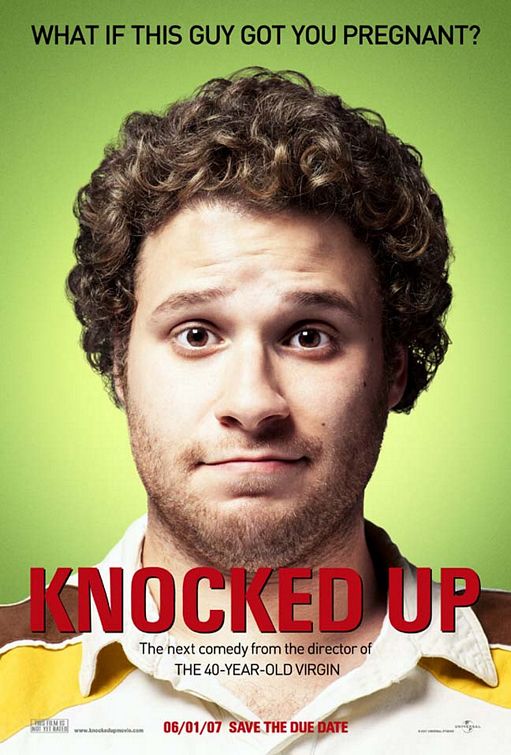

The first ads I saw for Superbad were banner ads on MySpace. The film was advertised as “from the creators of Knocked Up,” provoking my immediate dismissal. Clearly this was going to be a cheap cash-in on Knocked Up’s success, starring two unknowns, one of whom I only knew from an obscure TV show nobody else had seen (yet). In reality, Superbad turned out to be the far superior film.

I don’t remember what turned me around on the idea, but certainly the TV ads helped, especially the ones with McLovin. Without giving away the best jokes, the campaign presented us with a teen movie with a very different, very teenage sense of humor. And then the actual movie took it to the next level. For that reason, Superbad is one of my top five favorite films, and probably always will be.

Most movies about teenagers suck because they’re not really about teenagers– they either exploit hoary old tropes to show nudity and wildness, or they simply put adult stories and characters in high school drag (remember that weird trend of teen adaptations of classic literature?). Superbad does neither. It is a raunchy comedy about teenage stupidity that’s also heartfelt, earnest, and empathetic.

Seth (Jonah Hill) and Evan (Michael Cera) are two best friends about to graduate high school and start college. Evan has been accepted to Dartmouth, which Seth couldn’t even dream of, and the fear of losing their friendship has kept them from dealing with the inevitable consequences of their separation. Instead, the two try to win the affections of their mutual crushes (Emma Stone and Martha McIsaac) by acquiring alcohol for their end-of-year party, with the help of dorky hanger-on Fogell (Christopher Mintz-Plasse) who has recently acquired a fake ID that would be convincing except that the name on the card simply reads “McLovin.”

From this starting point, Superbad is tight and controlled; director Greg Mottola blesses the film with a clearly-defined aesthetic that most comedies sorely lack. Over the course of a single day, a random encounter with two grossly irresponsible police officers (Bill Hader and Seth Rogen) sets the guys off on a desperate After Hours-esque adventure, forcing them to reconcile their friendship and their future.

I don’t want to give Superbad credit for what it doesn’t do, but that certainly contributed to its success at the time, and I’ve yet to see a teen movie that has followed in its footsteps in such a way.

First, Superbad is not a romance. Although the film has love interests (and Emma Stone and Jonah Hill really do have chemistry here), the main conflict is over a platonic friendship between two young men. The fact that so many have read gay subtext into this film says as much about the frequent homoeroticism of adolescence (and the movie definitely has fun with that) as it does about the fact that close male friendships don’t get a lot of love in Hollywood. And they should, because it’s a huge, huge part of growing up that never seems to get its due.

Second, the teenagers act like teenagers. They don’t look 25 or have perfect skin or hair, or wear the latest fashions from Paris. They do not exist in the preordained, personality-based Apartheid state that high school is typically depicted as. They talk like teenagers. They swear incessantly like teenagers, but they’re also very clever like teenagers can sometimes be. And the whole film is permeated by a very teenage anxiety: the idea that everybody seems to know what’s going on except you.

And that’s what really makes Superbad hold up. It’s written in good faith, really trying to tell a teenage story. Screenwriters Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg claim to have started the script when they were only 13 years old; obviously it went through many drafts as their perspectives and writing skills improved, but something very important managed to survive that process. They didn’t go into it hoping to imitate or capitalize on anything that came before, but simply make something new: a comedy of youth as youth sees it.

How Did It Do?

Superbad grossed $169.9 million against a $20 million budget– an uncommonly lean budget for an Apatow production, but it’s worth remembering that Apatow neither wrote nor directed. It earned a well-deserved 87% rating on RottenTomatoes, but failed to make any notable year-end lists, in contrast to Knocked Up, which was only slightly better-received at the time. This may be credited to the fact that Superbad ended up relying so heavily on the Apatow name, which had only become famous as a result of Knocked Up a few months before.

At the same time, a small contingent of critics took Superbad much more seriously than Knocked Up. Wesley Morris used the word “sophisticated” –in a negative review, no less. Stephen Farber compared it to American Graffiti and Y Tú Mamá También. The seeds for Superbad’s legacy were already sown.

Perhaps most astonishingly, Superbad, a raunchy teen sex comedy that broke the record for most utterances of the word “fuck” per minute, re-defined Seth Rogen as a cinematic renaissance man. Having co-written Superbad at 13 and having become a staff writer for a network TV series at 18, he went on to become a regular presence on both sides of the camera and on both the big and small screen, finally turning to directing with Evan Goldberg on This is the End and The Interview. So too have co-stars Jonah Hill and Emma Stone, who both broke out in the wake of Superbad’s success and have each received multiple Academy Award nominations.

This is what great comedy can do.

Next Time: 3:10 to Yuma